Oppressive social structures are coded into our feeds to alienate and harm marginalized identity dissidents in Latin America. How can we fight back?

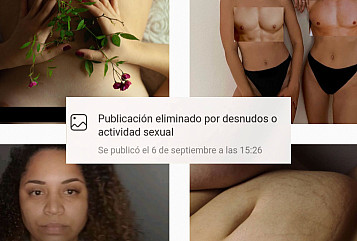

A sweet snap of lesbian love at a pride parade in Buenos Aires, Argentina is promptly purged from cyberspace. A shirtless childhood picture of a Black female Brazilian scientist triggers a restriction to the link feature. An artistic post by an Argentine-based photographer showcasing non-conforming female bodies quickly disappears. If you are an identity dissident in Latin America, this kind of social media censorship is commonplace. Since 2019, my Instagram feed has been flooded repeatedly with posts reporting platform censorship. As a tech worker who navigates the software development world, and an activist involved in digital security and digital rights, I couldn’t help but notice a pattern to whose content was censored.

I asked my family members in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, who are conservatives and staunch Bolsonaro supporters, if they’d ever encountered such messages on their social media accounts, but they said no. Evidently, this was not happening everywhere. Who else was experiencing such censorship? I asked a close circle of my friends to take a screenshot every time they saw a “community guidelines infringed” notice pop up on their feeds. We are journalists, tech workers, teachers, artists, and activists—but our professions seem secondary in this case. In the myriad of existing identity boxes, our group is “other”: we are mixed race, Black, Indigenous, fat, LGBTQIA+, transgender, and nonbinary.

“How will this kind of platform censorship impact our already vulnerable communities who use these platforms as communication channels and living archives?”

We are all Latin Americans, and we are all identity dissidents—we do not conform to the dominant gender, race, sexual orientation, and conservative political alignment norms. Seeing these censorship messages repeatedly is traumatic. It makes us feel out of place and space—uncomfortable, isolated, exhausted, and numbed. I wonder: how will this kind of platform censorship impact our already vulnerable communities who use these platforms as communication channels and living archives? What effect would this have on our collective memory as marginalized communities?

Codifying trauma

“Trauma, ” writes Canadian Gender Studies scholar Ann Cvetkovich, can be understood as a sign or symptom of a broader systemic problem, a moment in which abstract social systems can actually be felt or sensed.” I understand “algorithmic trauma” as the harm intentionally inflicted on end users through the byproducts of software design processes lacking guiding principles to counterbalance racial, gender, and geo-political hierarchies. Digital reality cries out for change as oppressive social structures are coded into the current engineered features, continuously alienating identity dissidents.

They suffer the systemic effects of being consistently censored and classified as “undesirable.” These labels serve as output data to train algorithms on how desired bodies must look and behave to be worthy of existing on social media. In addition, being digitally exposed to notifications with puzzling messages such as: “Your content infringes our community guidelines” causes trauma.

According to Cvetkovich, life under capitalism may manifest “as much in the dull drama of everyday life as in cataclysmic or punctual events.” The trauma of living under systemic oppression can present both in quotidian and extreme situations, and it can be intense or numbing. In this way, algorithmic trauma becomes a digital extension of the daily violence, racism, misogyny, and LGBTQIA+ phobia that identity dissidents face daily in the outside world. U.S. psychologist Margaret Crastnopol describes these virtual traumas as “small, subtle psychic hurts.” For example, a user might think: “How can I violate the community’s guidelines by simply posting pictures of my body? Am I not also a part of this community?”

Labor: who gets to design algorithmic trauma?

But who decides what is acceptable or not on social media? From the software development and product strategy level, the U.S. dominance of tech companies has been central to sustaining digital colonialism, a phenomenon that has far-reaching consequences for the Global South. For instance, most western social media platforms operate from Silicon Valley, California, in the U.S.A., yet according to data published in 2021, 88% of Instagram users reside outside of the U.S.A. Geo-politics influences the software development and decision-making processes, aggravating the issue of unequal exposure in digital spaces.

Furthermore, tech companies’ workforces do not represent their audience’s diversity. For example, Facebook and Twitter employees consist of Bay Area, California residents glowing in the pacific lights—digital nomads untethered to the lands they gentrify. According to the Diversity Update report, Facebook’s U.S.-based employees are 39% white and 45% Asian-American. Until a few years ago, Facebook grouped Hispanic and Black people together when divulging employee data, and it is unclear if they grouped non-Hispanic Latinos in that data—or if they even care to know the difference.

South African sociologist Michael Kwet defines Silicon Valley as an imperial force. Made-in-California technology affects identity dissidents who remain trapped as third-party observers in the looking glass of their own lives. In Decolonizando Valores (Decolonizing Values), Brazilian philosopher Thiago Teixeira talks about the “colonial mirror, ” a destructive composition promoting hate for the “other.” In this case, “other” refers to anyone not white, male, cis-heterosexual, or located in territories that are economically privileged. Facebook’s recruiting data and the application of its community guidelines seem to reflect the colonial mirror, dictating the identity of who gets to define the code and who suffers algorithmic trauma.

Technology professionals from the Global South have seen a rise in job offers from U.S. and European companies in the last years, enforcing labor inequalities. As a result, national industries are overwhelmed by foreign options and can’t develop locally-centered innovations. According to an international nonprofit journalism organization, Rest of the World, U.S. companies “pillage tech talent” in Latin America and Africa, thereby undermining the local endeavors that can’t afford to offer higher salaries. This strategy serves the Global North market, getting a cheap but highly qualified labor force. However, workers from the South don’t fill positions of strategic importance. Instead, they remain as scalable code writers and problem solvers.

In parallel, numerous Latin American activists and scholars tackle how algorithms exacerbate unequal representation and exposure online. For example, a coalition of civil society organizations across the continent published Standards for democratic regulation of large platforms, a regional perspective suggesting models for co-regulation and policy recommendations. They focus on transparency, terms and conditions, content removal, right to defense and appeal, and accountability. This collectively sourced report acknowledges these companies’ power over the flow of information on the Internet and their role as gatekeepers.

Coding Rights, a Brazilian research organization, shared better pathways for Decolonizing AI: A transfeminist approach to data and social justice. They foster an online social environment free of online gender violence, allowing identity dissidents to express themselves openly. Similarly, Derechos Digitales, a digital rights organization in Latin America, produced the 2021 Hate Speech in Latin America report, analyzing regulatory trends in the region and risks to freedom of expression. They recommend—what to the neoliberal platforms must sound almost radical—that content published on social networks and internet platforms must conform to global human rights standards. This should apply not only to what is allowed or not but also to transparency, minimum guarantees of process, right to appeal, and information to the end user.

A further report, Content Removal: inequality and exclusion from digital civic space, by Article 19 Mexico, an independent organization, highlights a few essential points to understanding algorithmic trauma on the identity dissident communities. The authors view content removal as a form of violence enacted on the vulnerable. Consequently, it “contributes to generating a climate of exclusion, censorship, self-censorship and social apathy in the digital environment.” The report includes a survey in which participants describe sensations of anxiety and vulnerability, such as: “I limit myself to publishing certain things or images because (…) I don’t have thick skin and [violence] affects me.” Another person writes: “We reach spaces [the social networks] that are not so safe. So I have censored myself so as not to expose myself to the removal of content.”

“Unsurprisingly, most of the attempts to challenge the status quo come from the margins and not from positions of power.”

Community design: from trauma to healing

In an industry where people designing the harm are almost always not those who bear the brunt of it, we desperately need a social justice perspective to lead software development and redesign our online experiences. Yet, unsurprisingly, most of the attempts to challenge the status quo come from the margins and not from positions of power.

The collectively envisioned Design Justice framework puts forward principles to rethink design processes and to center people marginalized by design and its users. The Design Justice Network, initiated in Detroit, U.S.A. by 30 designers and community organizers engaged in social justice, draws on liberatory pedagogy practices and Black Feminist Theory.

It proposes to measure design’s impact by asking: “Who participated in the design process? Who benefited from the design? And who was harmed by design?” These principles guided the development of the social media initiative Lips Social, founded by U.S. social algorithm researcher Annie Brown. The platform originated as a response to communities of sex-positive artists and sex workers fed up with Instagram’s censorship and online harassment. Once on the app, a message greets us, asserting the user’s—and not an algorithm’s—control of what we would prefer to see in the news feed, and asking us to choose between a set of predetermined categories of content such as #selflove or #photography. This seemingly simple design feature reflects the deep respect and understanding of the community it serves. Adding a trigger warning label also mitigates what can constitute traumatic content for the user. Through design and code, Lips Social is helping its community heal, connect, and economically sustain itself.

Reimagining can be a powerful design exercise to counterbalance hegemonic technologies. In an effort to shape more inclusive experiences, Coding Rights developed The Oracle for Transfeminist Technologies, a speculative tool using divination cards to collectively “envision and share ideas for transfeminist technologies from the future” and redesign existing products. The cards invite players to apply values such as solidarity, resilience, or horizontality, while simultaneously provoking reflection on their positionality. Given a particular situation as amplifying the narratives of women and queer people, players try to rethink and reclaim pornography or defend the right to anonymity online.

Another example is the color-picker tool by Safiya Umoja Noble, an internet studies scholar from the U.S.A., who created “The Imagine Engine” as a way of searching for information online. This color-picker tool calls attention to its findability by focusing on nuanced shades of information, making it easier to identify the limits between news, entertainment, pornography, and academic scholarship.

“We must acknowledge that algorithmic trauma is a consequence of software development processes and business strategies underpinned by colonial practices of extractivism and exclusion.”

Several alternatives to mitigating the harms already reproduced in systems are surfacing. Algorithmic Justice League is a U.S.-based organization combining art and research to illuminate the social implications of artificial intelligence. In their recent report, they spotted a trend in Bug Bounty Programs BBP, events sponsored and organized by companies to monetarily compensate individuals reporting bugs and surfacing software vulnerabilities, some of which may have caused algorithmic harm. The AJL provided a set of design levers and recommendations for how to shape BBPs for their discovery and reduction.

A few concerns also arise as this strategy might shift these platforms’ attention and responsibilities to the security community. Suddenly, it puts the burden of solving the coded oppression on people who have been systematically excluded from designing technology and are often targeted by it. However, to engender a structural change, we must acknowledge that algorithmic trauma is a consequence of software development processes and business strategies underpinned by colonial practices of extractivism and exclusion. These strategies inhibit the development of autonomous and collective solutions from and for the Global South.

Unionizing as a pathway to collective memory

In the digital realm, colonialism is perpetuated through proprietary software practices, data extractivism, corporate clouds, monopolized Internet and data storage infrastructure, and AI used for surveillance and control. All of this is implemented through content moderation, an automated process of deciding on what and who can participate in the digital space. Social media companies claim on paper that their policies guarantee the preservation of universal human rights; however, algorithmic surveillance and trauma are often driven by business priorities or political pressures. As a result, moderation policies frequently target the viewpoints of marginalized communities, at risk of over-enforcement. Notably, within the Latin-American context, moderators’ lack of in-depth knowledge of the local languages and socio-political milieu makes social media moderation subject to overwhelmingly biased discretionary decisions. In addition, anticipating certain moderation practices, communities shift their self-representation, impacting how they will be remembered in the future.

“Anticipating certain moderation practices, communities shift their self-representation, impacting how they will be remembered in the future.”

Instagram feeds, Twitter threads, and Facebook posts become data archives and collective memories. These corporations are becoming the record keepers of each community, and of individual memory itself, while there is still a total lack of transparency regarding content moderation policies.

Using open source technology is a possible response, contributing to design efforts to archive and safeguard content and history, and helping preserve context, narrative, and ownership. Critically reflecting on the idea of open source, we must ensure data collection transparency for future accountability. We desperately need decentralized, Global South developed, collaboratively owned, and maintained digital products outside the hegemonic platforms. This way, users can get greater autonomy to control what they want—and, more importantly, what they don’t want—to see and discover. They can also indicate what they would like to be remembered by, as well as how they prefer to have their data used in future research. Moreover, these design features minimize the risk of intentionally inflicting algorithmic trauma since this proposed software design process would be trauma-informed, centering on identity dissidents’ experiences.

“Designing algorithms and online experiences based on respect, and centering on human rights and care could foster a less traumatic environment for identity dissidents and, in doing so, improve the experience for all.”

The emphasis on the importance and input of labor in preventing the design of algorithmic trauma is essential to charting the way forward. There must be a shift in power in the technology industry to invite new processes that put the workers affected by these technologies to the forefront. There have been a few–mostly unsuccessful–attempts at unionizing by tech employees in Google, Amazon, Pinterest, and Salesforce in North America and Western Europe. Although the tech worker unions in Latin America haven’t yet raised these techno-societal issues, the gig economy workforce—vulnerable to unethical and exploratory tech policies and suffering from algorithmic trauma—has been organizing and protesting, demanding better work conditions be designed into these systems. Examining these proposals shows that better experiences are possible, and that the process directly informs the product’s impact. However, its clear limitations are the industry’s will, the technical scale for decentralized products, and financial sustainability—an impossibility given the monopoly of current tech companies.

The weight of responsibility could be directed to the workers building these harmful technologies. Once unionized, they could bring these uncomfortable conversations about harm and trauma directly into the development war room to the decision-making managers. The software development processes, leadership teams, and strategists in the digital economy platforms must embrace the need for responsible algorithm building. Otherwise, it becomes an endless loop of coding inequalities perpetuating digital colonialism at tech team meetings worldwide. Designing algorithms and online experiences based on respect, and centering on human rights and care could foster a less traumatic environment for identity dissidents and, in doing so, improve the experience for all.

Oct 26, 2022

Isabella Barroso (she/her)) is a journalist, researcher, technologist, and digital security instructor for activists. She researches the intersection of society, technology, and dissident communities. As the creator of the Guardians of the Resistance project, her current focus lies in the implications of content moderation policies of social media platforms on the memory of dissident communities in Abya Yala and the impact of this in on their counter-archiving practices. Her ongoing research project has created Guardiãs da Resistência, a podcast in Portuguese that wants to connect and share the knowledge of those who weave and preserve dissident memories in the continent.

This text was produced as part of the Coding Resistance Fellowship.