Article by by KAUSHIK PATOWARY

Original post available here

Computer technology from yesteryears look comically primitive and bulky. One popular image frequently shared in social media sites show a large cupboard-sized box lifted on to the cargo bay of a Pan American Airways flight. The caption accompanying the image identifies the box as the IBM 305 RAMAC, the world’s first commercial hard disk developed in 1957. It had a whooping capacity of only 5 megabytes.

In the early days of computing, memory technology permitted a capacity of very few bytes. The first electronic computer developed during the Second World War to help the military calculate artillery firing tables used vacuum tubes to store data. John Presper Eckert then invented a complicated device using mercury-filled glass tubes and quartz crystals that could store up to a few hundred thousand bits—a vast improvement from early memory technologies.

In the late 1940s, Frederick W. Viehe, an amateur inventor from Los Angles, filed patent for a new kind of memory that used tiny transformers to store data. This was improved substantially by Harvard physicist An Wang, and later by Jay Forrester and Jan A. Rajchman in the early 1950s, leading to the development of the magnetic core memory. This new memory technology was the first non-volatile memory—a memory that doesn’t lose data when it loses power— to be developed. It was used extensively in the US Navy’s Whirlwind computers for real-time aircraft tracking.

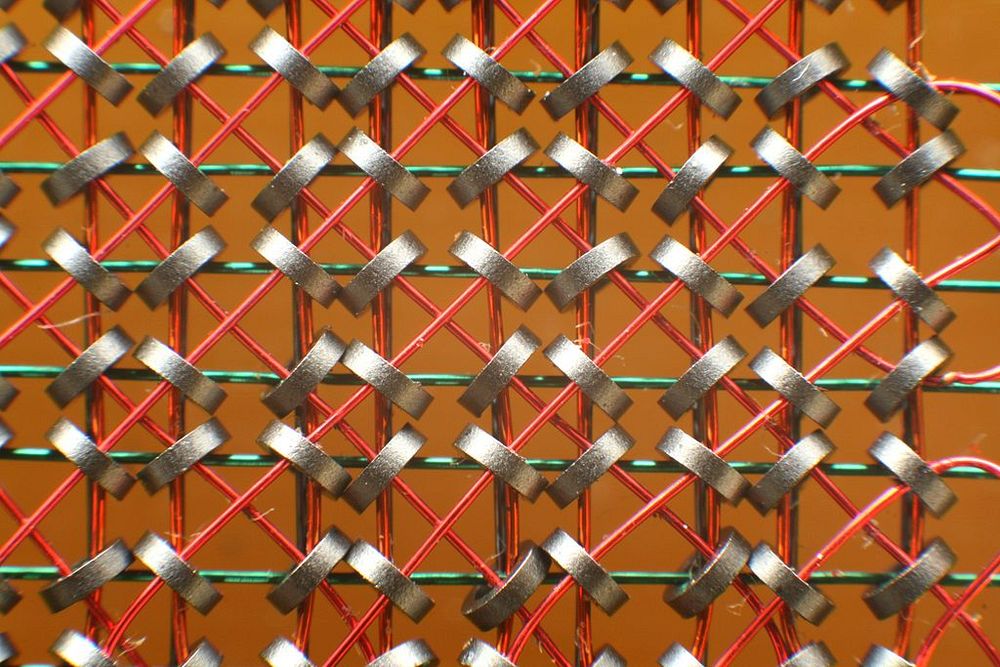

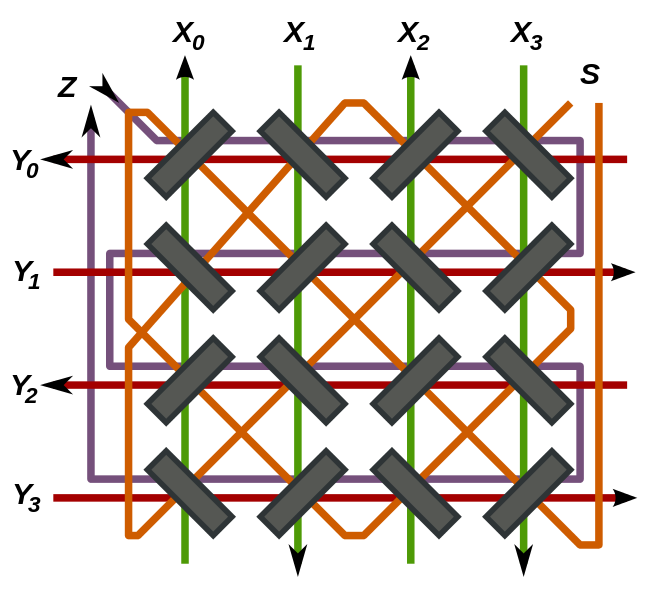

Magnetic core memory consists of tiny donuts of ferrite material strung on wires into arrays. Each donut could store a bit, and the value of the bit (zero or one) was identified by the direction of their magnetic flux. The wires that ran through the holes in the donuts could both detect (that is, read) and change (that is, write) the magnetization of the cores. Core memory became the dominant memory technology during the first two decades of the Cold War. But manufacturing it was a delicate job. The cores were tiny and had to be threaded by steady hands using magnifying glasses. As cores got smaller, engineers joked that new cores were made from the holes punched out of the previous generation of cores.

A core memory module with a capacity of 128 bytes. Photo: Konstantin Lanzet/Wikimedia Commons

Close-up of a core memory module. Photo: Konstantin Lanzet/Wikimedia Commons

Diagram of a 4×4 plane of magnetic core memory in an X/Y line coincident-current setup. X and Y are drive lines, S is sense, Z is inhibit. Arrows indicate the direction of current for writing. Diagram by Tetromino/Wikimedia Commons

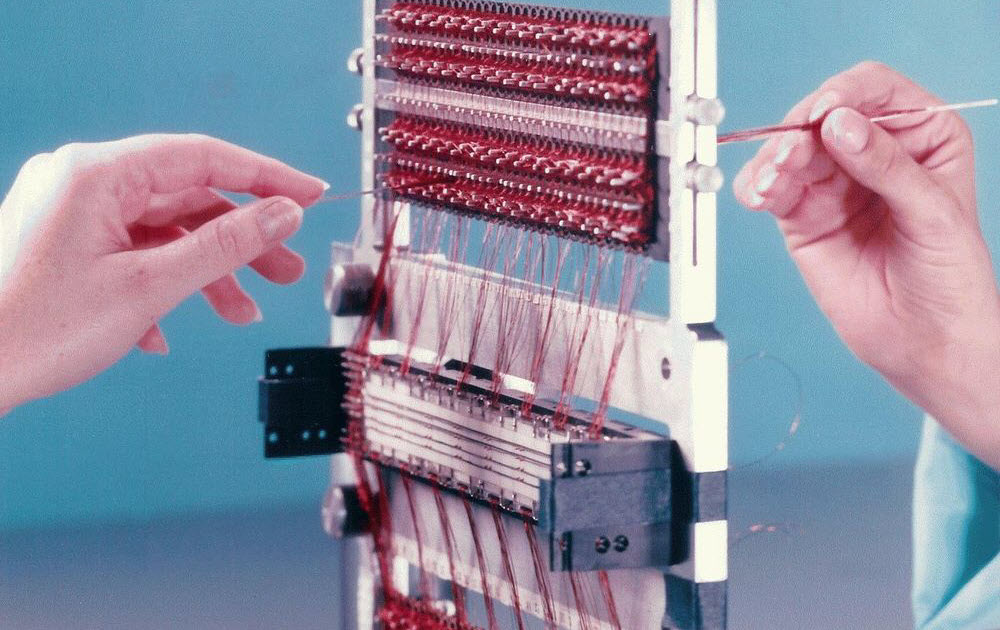

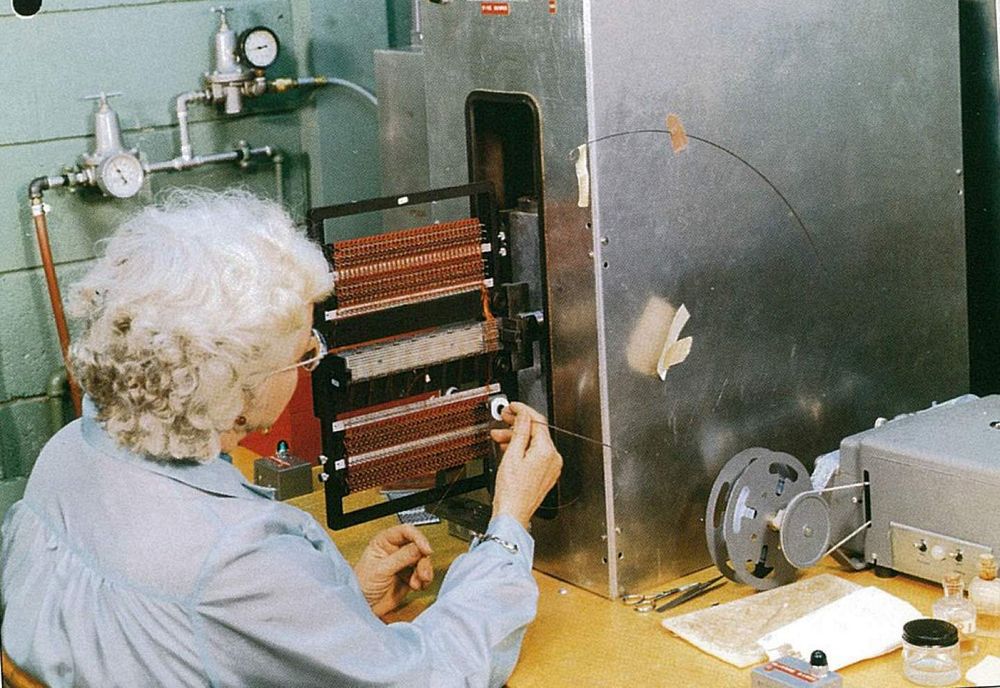

Like all crafts involving weaving, sewing and other forms of textile making that has been historically associated with women, the job of weaving core memory was also entrusted to women. During the first Apollo missions, the software of the Apollo Guidance Computer was physically weaved into a high-density storage called “core rope memory”, which was similar to magnetic core memories. To build the memories, NASA hired skilled women from the local textile industry as well as from the Waltham Watch Company, because of the precision needed to work around the cores with a needle. Sitting across each other at long desks, these women passed wires back and forth through a matrix of eyelet holes, each comprising a magnetic core bead. Passing a wire through the core created a “one, ” while bypassing the core created a “zero”.

The core rope memory was nicknamed “LOL memory”, where LOL stood for the «Little Old Ladies» who assembled it. They were supervised by “rope mothers”, who were often males. But the rope mother’s boss was a woman named Margaret Hamilton.

Margaret Hamilton was the director of the Software Engineering Division of the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, which developed on-board flight software for NASA’s Apollo space program. One of Hamilton’s chief contributions to Apollo mission was to devise a way to deal with computer errors. In the 1960s there were few formalized guidelines about how to write, document, and test complex software. But the Apollo software was remarkably error-free. What weren’t were humans.

During the landing sequence of Apollo 11, the astronauts inadvertently left the rendezvous radar switch on, overloading the computer. Hamilton had foreseen such an emergency and incorporated an error-detecting-and-correcting mechanism which allowed the overloaded Lunar Module computer to shed unimportant tasks and focus on steering the descent engine.

“If the computer hadn’t recognized this problem and taken recovery action, ” Hamilton later wrote to the Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming, “I doubt if Apollo 11 would have been the successful moon landing it was.”

If you want to learn more about how magnetic core memory works, the National Science Foundation of Florida has an interactive tutorial on this page.

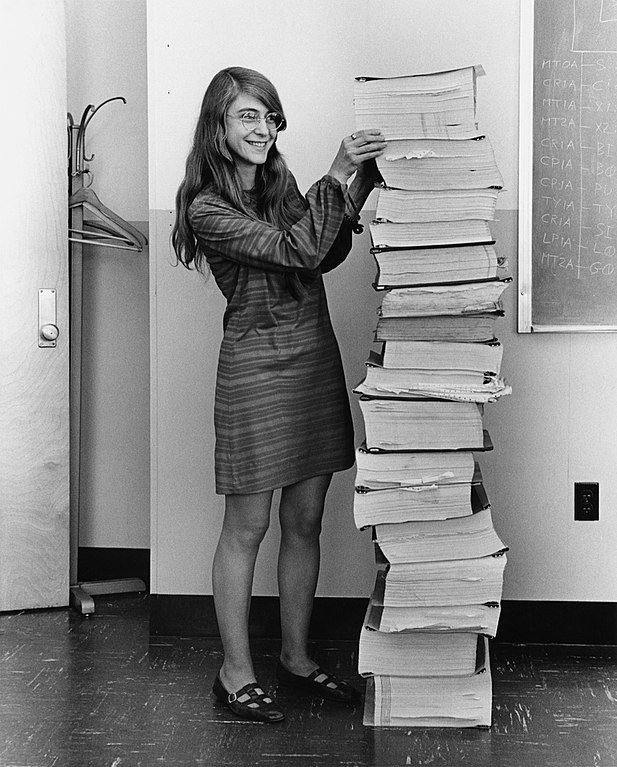

Margaret Hamilton standing next to the navigation software that she and her MIT team produced for the Apollo Project.

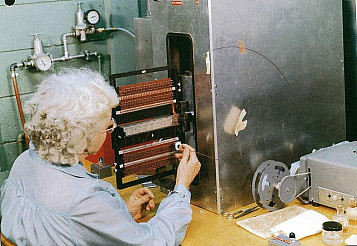

An unknown woman stringing the wiring components of the Apollo Guidance Computer memory.

An unknown woman stringing the wiring components of the Apollo Guidance Computer memory.

A technician weaving the core ropes at the Raytheon plant in suburban Boston.

A fully wired tray A of the Apollo Guidance Computer.

A technician assembling the micrologic and core memory panels that make up the Apollo Guidance Computer into their housing.

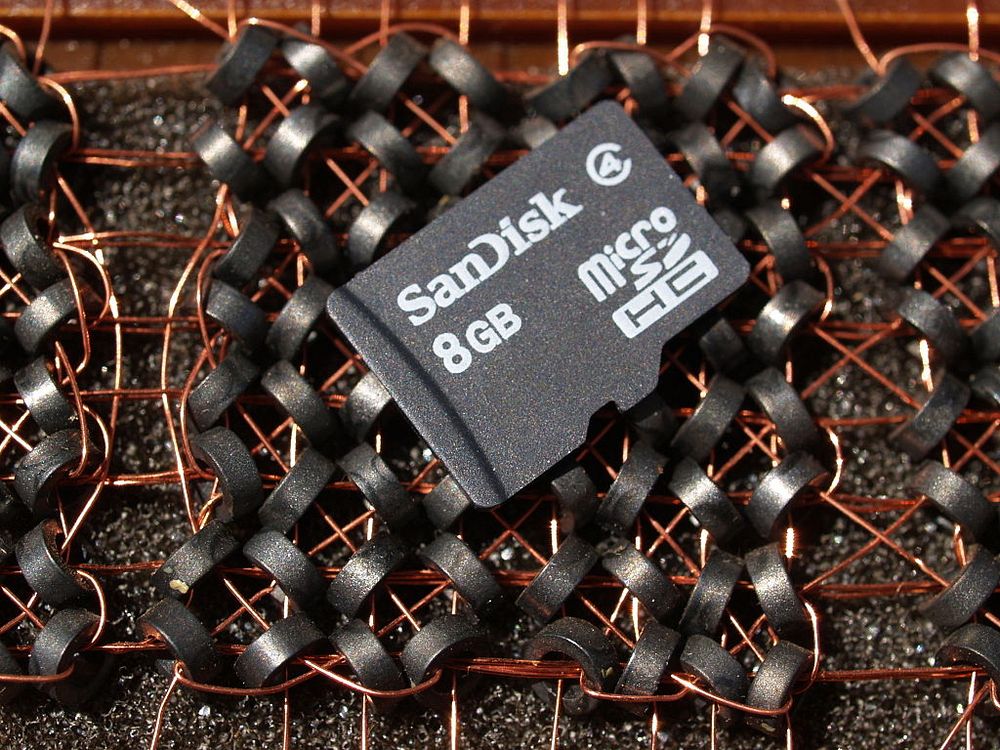

An 8-GB microSD card on top of 8-Bytes of magnetic-core memory. Photo: Daniel Sancho/Wikimedia Commons

References:

# Computer History Museum, https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/memory-storage/8/253

# Daniela K. Rosner et al. Making Core Memory, https://faculty.washington.edu/dkrosner/files/CHI-2018-Core-Memory.pdf

# Ken Shirriff’s blog, http://www.righto.com/2019/07/software-woven-into-wire-core-rope-and.html

# National Air And Space Museum, https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/rope-mother-margaret-hamilton

# Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic-core_memory

# IEEE Specturm, https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-history/space-age/software-as-hardware-apollos-rope-memory

# Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Hamilton_(software_engineer)