A woman was sexually harassed on Meta’s VR social media platform. She’s not the first—and won’t be the last.

Last week, Meta (the umbrella company formerly known as Facebook) opened up access to its virtual-reality social media platform, Horizon Worlds. Early descriptions of the platform make it seem fun and wholesome, drawing comparisons to Minecraft. In Horizon Worlds, up to 20 avatars can get together at a time to explore, hang out, and build within the virtual space.

But not everything has been warm and fuzzy. According to Meta, on November 26, a beta tester reported something deeply troubling: she had been groped by a stranger on Horizon Worlds. On December 1, Meta revealed that she’d posted her experience in the Horizon Worlds beta testing group on Facebook.

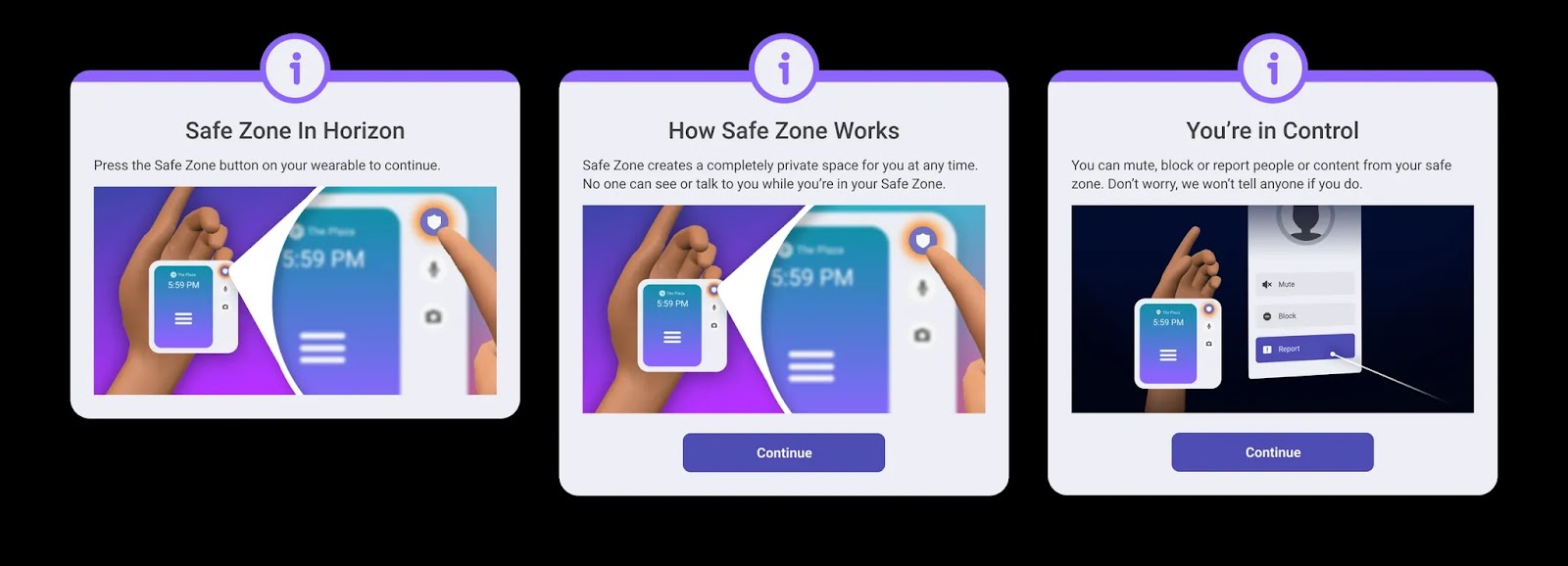

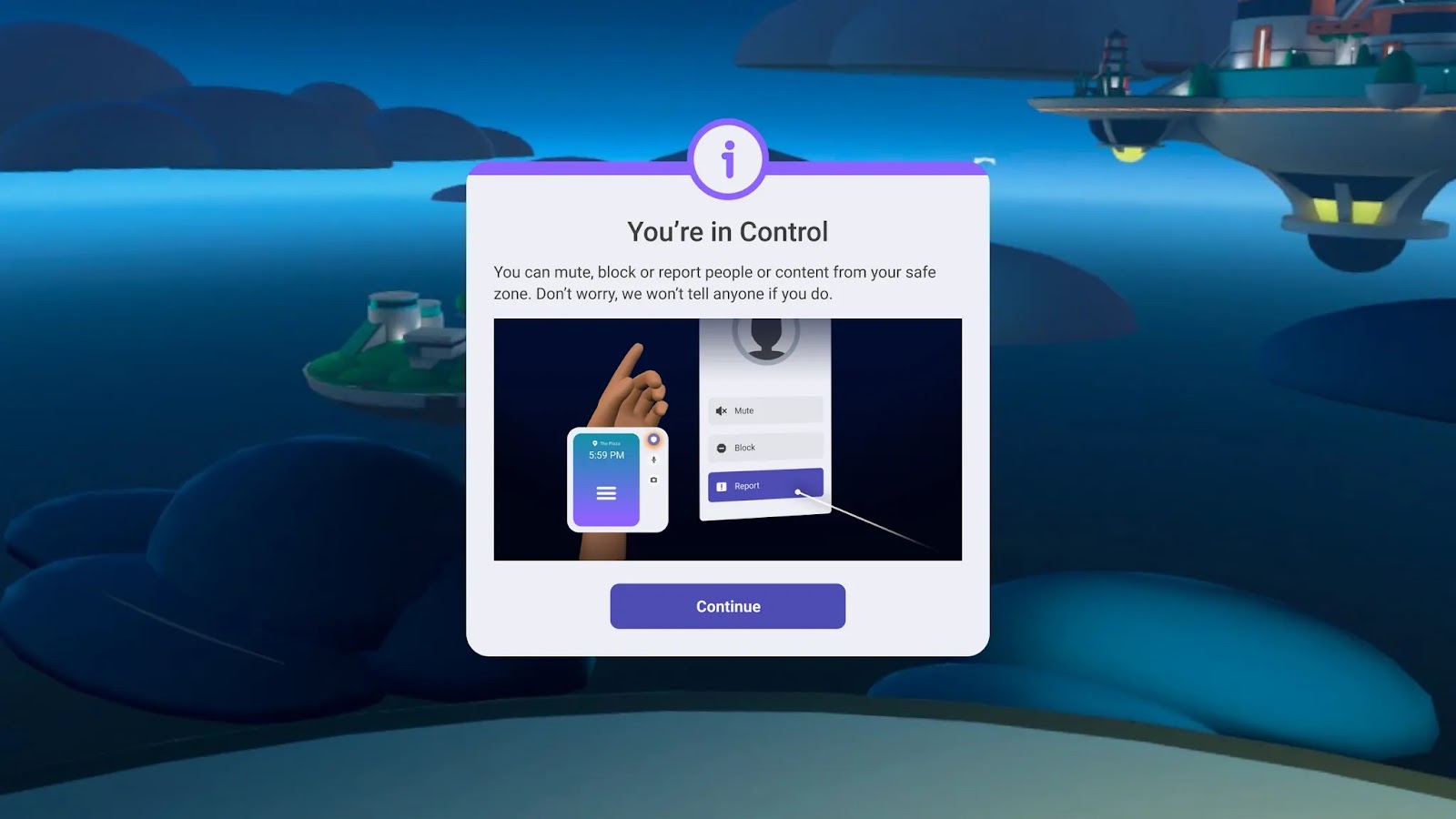

Meta’s internal review of the incident found that the beta tester should have used a tool called “Safe Zone” that’s part of a suite of safety features built into Horizon Worlds. Safe Zone is a protective bubble users can activate when feeling threatened. Within it, no one can touch them, talk to them, or interact in any way until they signal that they would like the Safe Zone lifted.

Vivek Sharma, the vice president of Horizon, called the groping incident “absolutely unfortunate, ” telling The Verge, “That’s good feedback still for us because I want to make [the blocking feature] trivially easy and findable.”

It’s not the first time a user has been groped in VR—nor, unfortunately, will it be the last. But the incident shows that until companies work out how to protect participants, the metaverse can never be a safe place.

“There I was, being virtually groped”

When Aaron Stanton heard about the incident at Meta, he was transported to October 2016. That was when a gamer, Jordan Belamire, penned an open letter on Medium describing being groped in Quivr, a game Stanton co-designed in which players, equipped with bow and arrows, shoot zombies.

In the letter, Belamire described entering a multiplayer mode, where all characters were exactly the same save for their voices. “In between a wave of zombies and demons to shoot down, I was hanging out next to BigBro442, waiting for our next attack. Suddenly, BigBro442’s disembodied helmet faced me dead-on. His floating hand approached my body, and he started to virtually rub my chest. ‘Stop!’ I cried … This goaded him on, and even when I turned away from him, he chased me around, making grabbing and pinching motions near my chest. Emboldened, he even shoved his hand toward my virtual crotch and began rubbing.

“There I was, being virtually groped in a snowy fortress with my brother-in-law and husband watching.”

Stanton and his cofounder, Jonathan Schenker, immediately responded with an apology and an in-game fix. Avatars would be able to stretch their arms into a V gesture, which would automatically push any offenders away.

Stanton, who today leads the VR Institute for Health and Exercise, says Quivr didn’t track data about that feature, “nor do I think it was used much.” But Stanton thinks about Belamire often and wonders if he could have done more in 2016 to prevent the incident that occurred in Horizon Worlds a few weeks ago. “There’s so much more to be done here, ” he says. “No one should ever have to flee from a VR experience to escape feeling powerless.”

VR sexual harassment is sexual harassment, full stop

A recent review of the events around Belamire’s experience published in the journal for the Digital Games Research Association found that “many online responses to this incident were dismissive of Belamire’s experience and, at times, abusive and misogynistic … readers from all perspectives grappled with understanding this act given the virtual and playful context it occurred in.” Belamire faded from view, and I was unable to find her online.

A constant topic of debate on message boards after Belamire’s Medium article was whether or not what she had experienced was actually groping if her body wasn’t physically touched.

“I think people should keep in mind that sexual harassment has never had to be a physical thing, ” says Jesse Fox, an associate professor at Ohio State University who researches the social implications of virtual reality. “It can be verbal, and yes, it can be a virtual experience as well.

Katherine Cross, who researches online harassment at the University of Washington, says that when virtual reality is immersive and real, toxic behavior that occurs in that environment is real as well. “At the end of the day, the nature of virtual-reality spaces is such that it is designed to trick the user into thinking they are physically in a certain space, that their every bodily action is occurring in a 3D environment, ” she says. “It’s part of the reason why emotional reactions can be stronger in that space, and why VR triggers the same internal nervous system and psychological responses.”

That was true in the case of the woman who was groped on Horizon Worlds. According to The Verge, her post read: “Sexual harassment is no joke on the regular internet, but being in VR adds another layer that makes the event more intense. Not only was I groped last night, but there were other people there who supported this behavior which made me feel isolated in the Plaza [the virtual environment’s central gathering space].”

Sexual assault and harassment in virtual worlds is not new, nor is it realistic to expect a world in which these issues will completely disappear. So long as there are people who will hide behind their computer screens to evade moral responsibility, they will continue to occur.

The real problem, perhaps, has to do with the perception that when you play a game or participate in a virtual world, there’s what Stanton describes as a “contract between developer and player.” “As a player, I’m agreeing to being able to do what I want in the developer’s world according to their rules, ” he says. “But as soon as that contract is broken and I’m not feeling comfortable anymore, the obligation of the company is to return the player to wherever they want to be and back to being comfortable.”

The question is: Whose responsibility is it to make sure users are comfortable? Meta, for example, says it gives users access to tools to keep themselves safe, effectively shifting the onus onto them.

“We want everyone in Horizon Worlds to have a positive experience with safety tools that are easy to find—and it’s never a user’s fault if they don’t use all the features we offer, ” Meta spokesperson Kristina Milian said. “We will continue to improve our UI and to better understand how people use our tools so that users are able to report things easily and reliably. Our goal is to make Horizon Worlds safe, and we are committed to doing that work.”

Milian said that users must undergo an onboarding process prior to joining Horizon Worlds that teaches them how to launch Safe Zone. She also said regular reminders are loaded into screens and posters within Horizon Worlds.

But the fact that the Meta groping victim either did not think to use Safe Zone or could not access it is precisely the problem, says Cross. “The structural question is the big issue for me, ” she says. “Generally speaking, when companies address online abuse, their solution is to outsource it to the user and say, ‘Here, we give you the power to take care of yourselves.’”

And that is unfair and doesn’t work. Safety should be easy and accessible, and there are lots of ideas for making this possible. To Stanton, all it would take is some sort of universal signal in virtual reality—perhaps Quivr’s V gesture—that could relay to moderators that something was amiss. Fox wonders if an automatic personal distance unless two people mutually agreed to be closer would help. And Cross believes it would be useful for training sessions to explicitly lay out norms mirroring those that prevail in ordinary life: “In the real world, you wouldn’t randomly grope someone, and you should carry that over to the virtual world.”

Until we figure out whose job it is to protect users, one major step toward a safer virtual world is disciplining aggressors, who often go scot-free and remain eligible to participate online even after their behavior becomes known. “We need deterrents, ” Fox says. That means making sure bad actors are found and suspended or banned. (Milian said Meta “[doesn’t] share specifics about individual cases” when asked about what happened to the alleged groper.)

Stanton regrets not pushing more for industry-wide adoption of the power gesture and failing to talk more about Belamire’s groping incident. “It was a lost opportunity, ” he says. “We could have avoided that incident at Meta.”

If anything is clear, it’s this: There is no body that’s plainly responsible for the rights and safety of those who participate anywhere online, let alone in virtual worlds. Until something changes, the metaverse will remain a dangerous, problematic space.

By Tanya Basu

Photo: Getty