Original post published in Medium

A feminist approach to consent in digital technologies

by By Paz Peña and Joana Varon

It’s strange to think that two of the most important discussions today are around the same concept: consent. In one hand, the whole #MeToo movement has helped to resurface in the public opinion an old and never overcome debate on sexual consent, and in the other, the political scandal of Facebook–Cambridge Analytica has demonstrated (again) the futile exercise to consent on the use of our data in datafied societies dominated by a handle of transnational data companies.

Nevertheless, while these two discussions are happening at the same time, bridges between them are almost nonexistent. Moreover, when we talk about our sexual practices mediated by platforms (sexting, dating apps, etc), the discussion on how these two types of consent collide and what complexities come after that are almost always ignored. For example, in the policy debate on NCII (non-consensual dissemination of intimate images), the lack of consent is either almost entirely seen as a sexual offense or as a mere problem of data protection and privacy.

In order to shed a light on the matter, we are launching today, the research “Consent to our Data Bodies: Lessons from feminist theories to enforce data protection”. The goal was to explore how feminists views and theories on sexual consent can feed the data protection debate in which consent — among futile “Agree” buttons — seems to live in a void of significant meaning. Envisioned more as a critical provocation than a recipe, the study is an attempt to contribute to a debate on data protection, which seems to return over and over again to a liberal and universalizing idea of consent. This framework has already proved to be key for abusive behaviors by different powerful players, ranging from big monopolistic ICTs companies, like Facebook, to Hollywood celebrities and even religious leaders, such as the recent case of João de Deus, in Brazil.

On the other hand, feminist debates made it is clear that the liberal approach of individuals as autonomous, free and rational subjects is problematic in many ways, especially in terms of meaningful consent: this formula does not consider historical and sociological structures where consent is exercised. In this sense, a very rich question to pose for the data protection debate from a feminist perspective is “who has the ability to say no?”

“In this context, Perez considers something fundamental:

“it’s not just about consent or not, but fundamentally the possibility of doing so.”

Also in this regard, it seems interesting to recall what Sara Ahmed (2017) says about the intersectional approach towards an impossibility of saying “no”:

“The experience of being subordinate — deemed lower or of a lower rank — could be understood as being deprived of no. To be deprived of no is to be determined by another’s will”.”

If consent is a function of power, not all the players have the ability to negotiate nor to reject the conditions imposed by the Terms of Services (ToS) in platforms. In this framework, beyond “Agree” to the usage of our personal data, what most of people do is simply “Obey” the company’s will. Therefore, confronting the fantasy of digital technologies functioning as vehicles of empowerment and democracy, what we have are data societies where control is validated by a legal contract and a bright button of agreement.

The liberal framework of consent in data protection has been under scrutiny by important privacy scholars. Helen Nissenbaum asks for quitting the idea of “true” consent and, at the end, stop thinking on consent as a measure of privacy. She makes a call to drop out the simplification of online privacy and adopt a more complex context. Julie E. Cohen has a very similar approach. For her, to understand privacy simply as an individual right is a mistake:

“The ability to have, maintain, and manage privacy depends heavily on the attributes of one’s social, material, and informational environment” (2012). In this way, privacy is not a thing or an abstract right, but an environmental condition that enables situated subjects to navigate within preexisting cultural and social matrices (Cohen, 2012, 2018).“

From a contextual integrity framework to condition-centered frameworks, among others, the call of some of these scholars is to dismiss the liberal trap of “Notice and Consent” as a universal legitimating condition for data protection, and instead to protect privacy in the design of the platform rather than in the legal contracts.

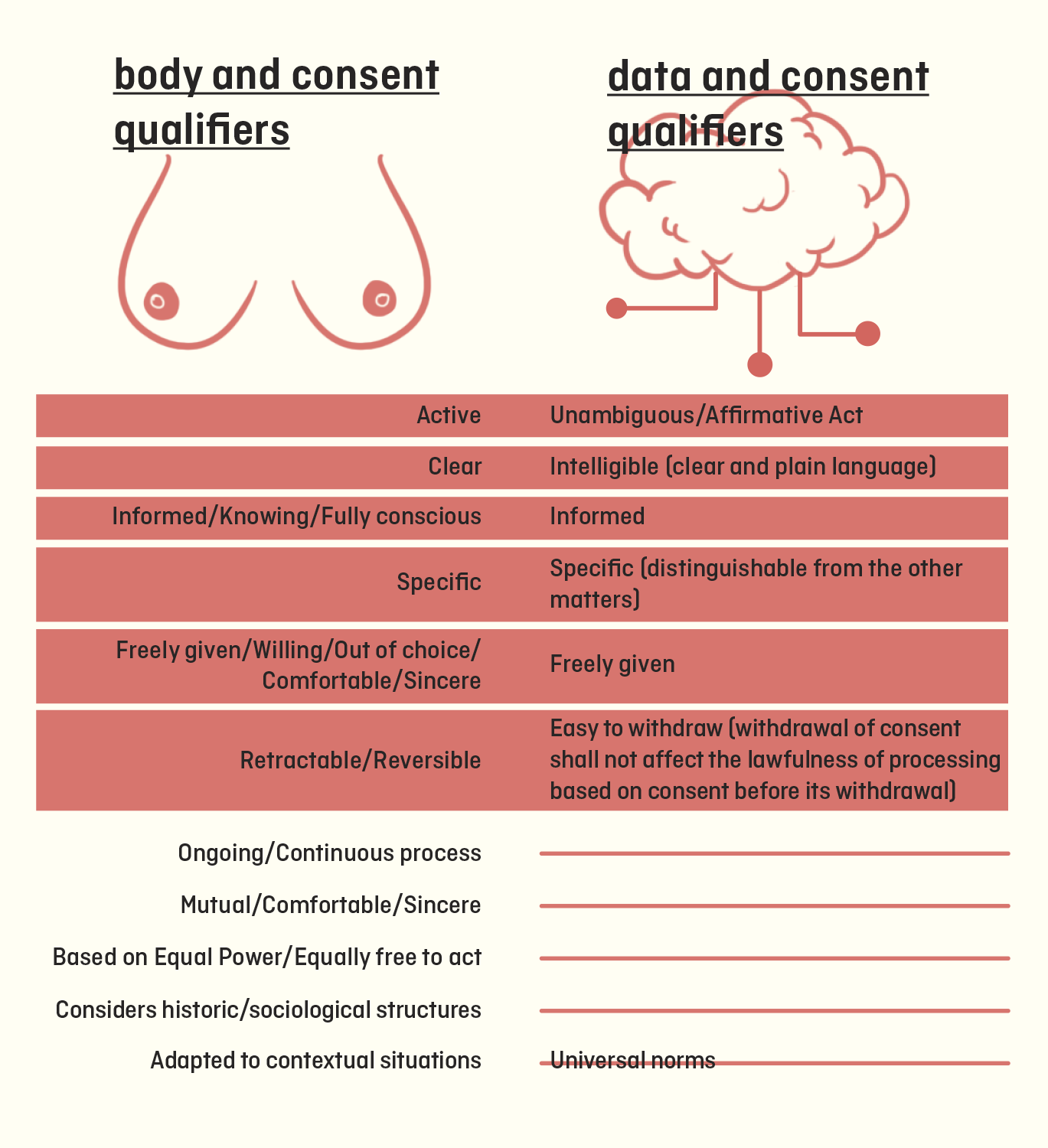

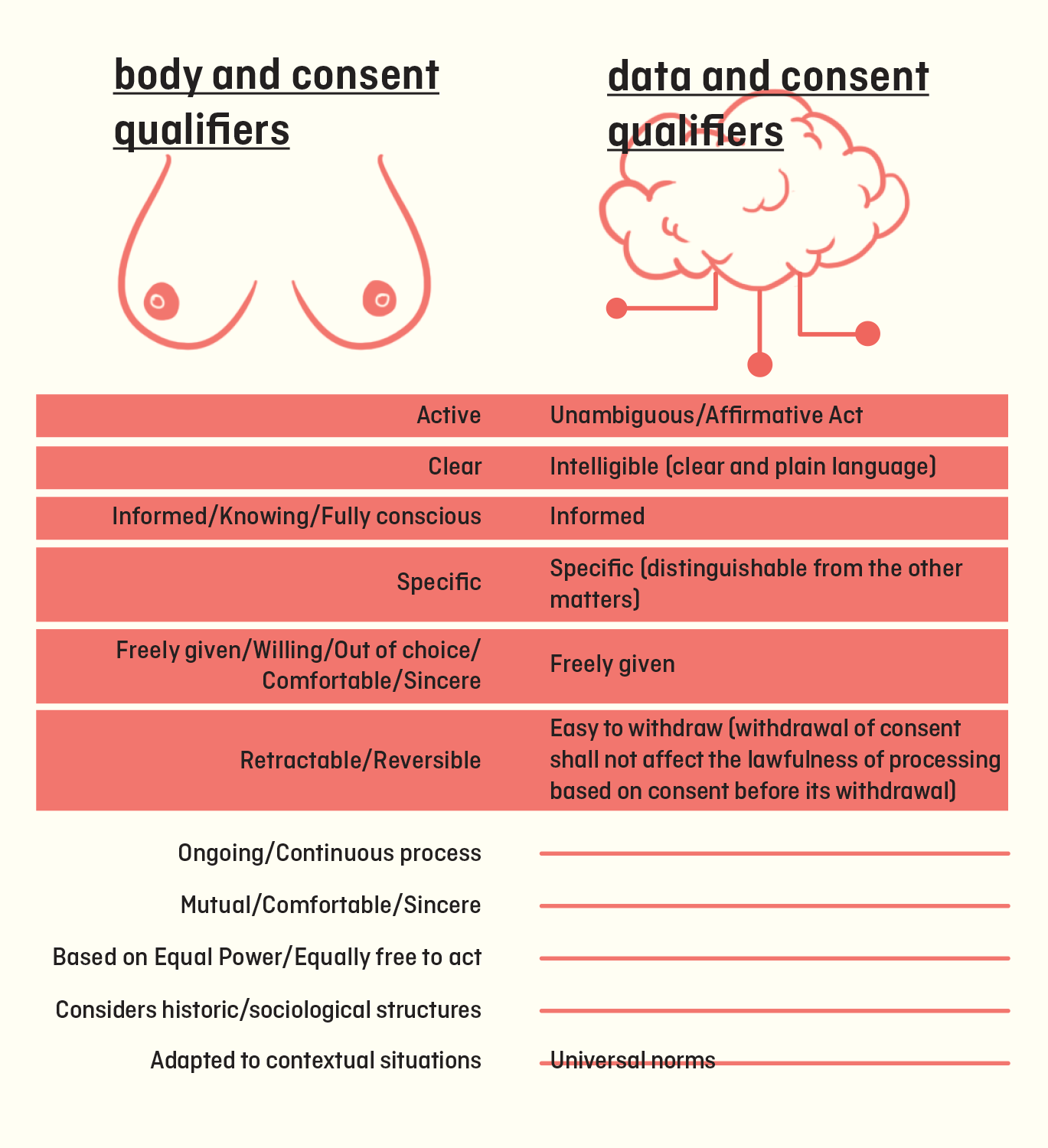

Sadly, meanwhile legal contracts are still a mechanism for social control, privacy and feminist activists should be pushing for strong changes in both ways: design and consent in ToS. In this sense, we have sketched a “matrix of qualifiers of consent from body to data” in order to start thinking creatively and collectively ways to ensure strong and contextually meaningful data protection standards for all users.

The matrix shows that while some of the qualifiers are overlapping in the debates of both fields, the list of consent qualifiers present in data protection debates, such as in the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), taken as a model for many privacy aware jurisdictions, falls short, disconsider some structural challenges and loosely compiles all qualifiers in one single action of clicking in a button.

What would be technical and legal alternatives if we we are up to think and design technologies that allow for tangible expression of all these qualifiers listed by feminist debates and, more important, consider that there are no universal norms if there are different conditions and power dynamics among those who consent?

We hope that the some of the finding from this research (available bellow) are just the beginning of a long and exciting feminist journey to collectively build a feminist framework for consent on the Internet. #FeministInternet

Full version of the research “Consent to our Data Bodies: Lessons from feminist theories to enforce data protection”, produced by Coding Rights with support of Privacy International and funding from the International Development Research Center is available here: https://codingrights.org/docs/ConsentToOurDataBodies.pdf

References for this blogpost (more references of the whole study in the research link right above)

Ahmed, Sara. 2017. “No”. feministkilljoys. https://feministkilljoys.com/2017/06/30/no/

Barocas, S., and Nissenbaum, H. 2009. “On Notice: The Trouble with Notice and Consent”. Proceedings of the Engaging Data Forum: The First International Forum on the Application and Management of Personal Electronic Information, October 2009.

Barocas, S., and Nissenbaum, H. 2014. Big “Data’s End Run around Anonymity and Consent”. In J. Lane, V. Stodden, S. Bender, & H. Nissenbaum (Eds.), Privacy, Big Data, and the Public Good: Fr

Cohen, Julie E. 2012. “WHAT PRIVACY IS FOR”. DRAFT 11/20/2012. 126 HARV. L. REV. (forthcoming 2013)

Cohen, Julie E. 2019. “Turning Privacy Inside Out”. Forthcoming, Theoretical Inquiries in Law 20.1 (2019).

Nissenbaum, Helen. 2011. “A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online”. Daedalus 140 (4), Fall 2011: 32–48.

Pérez, Yolinliztli. 2016. “Consentimiento sexual: un análisis con perspectiva de género”. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 78, núm. 4: 741–767.