Original post published by Dan Maloney here

For most of human history, musical instruments were strictly mechanical devices. The musician either plucked something, blew into or across something, or banged on something to produce the sounds the occasion called for. All musical instruments, the human voice included, worked by vibrating air more or less directly as a result of these mechanical manipulations.

But if one thing can be said of musicians at any point in history, it’s that they’ll use anything and everything to create just the right sound. The dawn of the electronic age presented opportunities galore for musicians by giving them new tools to create sounds that nobody had ever dreamed of before. No longer would musicians be constrained by the limitations of traditional instruments; sounds could now be synthesized, recorded, modified, filtered, and amplified to create something completely new.

Few composers took to the new opportunities offered by electronics like Daphne Oram. From earliest days, Daphne lived at the intersection of music and electronics, and her passion for pursuing “the sound” lead to one of the earliest and hackiest synthesizers, and a totally unique way of making music.

WHEN YOU’RE RIGHT, YOU’RE RIGHT

When a medium accurately predicts your eventual career at a séance hosted by your father, there’s a good chance your life will be more interesting than usual. The fact that Daphne Oram, born in 1925 in Wiltshire, England, had always been musical, concentrating on the piano, was probably a tip-off used by the later-debunked mystic in making his prediction, but the proclamation was just what the 17-year-old nursing student needed to change the course of her life, and she did so in dramatic fashion.

With World War II raging, Daphne turned down an opportunity to study at the Royal College of Music to take a position with the BBC in 1942 as a music balancer, a position we’d probably refer to as a sound engineer these days. She was primarily responsible for setting up microphones for live performances and mixing the sound. Another part of Daphne’s job was to follow along with a vinyl record as the orchestra played, ready to switch to the recording seamlessly in case anything went wrong with the live performance.

Tape recorders would have eased Daphne’s job considerably, but they weren’t widely available until the 1950s. When they were, Daphne took to tape technology right away, seeing that it had the potential for not only recording music but for creating it. After hours, Daphne would experiment with tape recorders and other sound gear. She’d record short tones from sine wave generators onto tape loops and record the effects of playing them back at various speeds. More complicated sounds, like single notes from a clarinet or even environmental sounds like splashing water, were recorded and mixed with other tones, sometimes even played backward for unusual effects.

All of Daphne’s musical experimentation went unnoticed by BBC management. By the late 1950s, Daphne had been promoted to studio manager, and along with fellow recording engineer Desmond Briscoe, she began campaigning for the creation of a new electronic music department, much like one she had seen during a trip to Paris. BBC management couldn’t have cared less about their efforts since they felt that they had all the music they needed.

But other producers were interested in Oram and Briscoe’s techniques, and in 1958 the BBC relented. They named the new department “The BBC Radiophonic Workshop, ” pointedly avoiding any reference to music so as not to upset the union musicians the Beeb depended on. The group was to concentrate on providing electronic sound effects for BBC radio and television programming, a mandate which grated on Daphne, who felt that the entire point was to create music, not blips and bleeps for commercials and science fiction shows.

SEEING THE MUSIC

Within a year of cofounding the Workshop, Daphne quit the BBC and set out on her own, with an entirely new vision of electronic music. Early in her BBC career, she had seen an oscilloscope used to display an audio signal. Rather than electronically paint an image of sound on a screen, she wondered if it would be possible to do the reverse – to take a painting and electronically turn it into music.

To explore this, Daphne set up the Oramics Studios for Electronic Composition. She paid the bills with jingle and commercial work using the tape recorder techniques she had pioneered at the BBC, but her passion was creating a new musical instrument, one that would let her translate drawn images directly to music. She called her as-yet unrealized process Oramics, and spent the early 1960s developing it. Her idea was to draw patterns directly onto 35-mm film stock that could be read by a photocell, similar to the way a movie soundtrack was recorded. But instead of recording a sound, the curves and squiggles on the film would control oscillators and filters to create sound.

As technically adept as Daphne was, her Oramics machine remained unfinished until 1965, when she got in touch with a fellow sound engineer, the delightfully named Graham Wrench. They had met years before, and she asked him to take a look at her machine. She explained the concept, and Graham instantly saw how the cathode ray tube (CRT) technology that he had worked on as an RAF radarman could be put to use. He signed on with Daphne, and together they brought the Oramics machine to life.

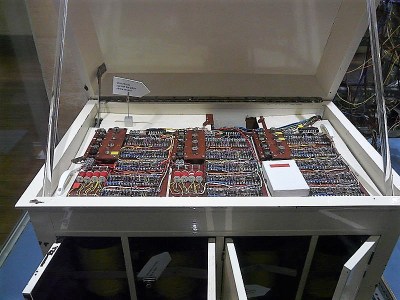

The working system used an oscilloscope CRT to scan each frame of the film. The film with its drawn patterns passed between the CRT, tracing out a horizontal line along its bottom, and a photomultiplier tube. The photomultiplier tube controlled the vertical position of the trace, increasing the voltage on the Y-axis until the trace was visible through the patterns on the film. The Y-axis voltage was sent through a complex battery of filters to audio amplifiers.

The whole machine, from Graham’s CRT-based waveform scanners to the pitch controls to the film-handling machinery, was enormous and fussy. It was built on a shoestring budget funded by grants, meaning that Daphne and Graham cut corners wherever possible. When phototransistors proved too expensive for the control tracks needed, Graham cut open the cases of regular transistors to make them light-sensitive. Everything about the machine was a work in progress, with bits added a Daphne came up with a new idea or deleted as her interests changed.

MOVING ON

Despite all the years of work she put into Oramics, Daphne only recorded a handful of compositions using the various incarnations of her machine. Oramics became less important to Daphne once the 1970s rolled around, perhaps because the technique was cumbersome and becoming outdated as electronics technology progressed. She did try to revive the Oramics technique in software as the PC age dawned in the 1980s, but by then synthesizers and sequencers had taken a completely different direction that was more accessible to musicians than her method.

Oramics came and went, a brief flash of genius in the long history of musicians finding a way to make new sounds. We’re left only with the remains of Daphne’s machine, now relegated to museum-piece status, and the ghostly, throbbing, echoing compositions that came from the machine that could turn drawings into music.

Posted in Biography, Featured, Musical Hacks, Original Art, SliderTagged amplifier, crt, filter, flying-spot, Oramics, photomultiplier, synthesizer, waveform