Imagine having to program your computer by rewiring it. For a brief period of time around the mid-1940s, the first general-purpose electronic computers worked that way. Computers like ENIAC initially had no internal storage for code. Programming it involved manipulating thousands of switches and cables. The positions of those switches and cables were the program.

Kathleen Booth began working on computers just as the idea of storing the program internally was starting to permeate through the small set of people building computers. As a result, she was one of the first programmers to work on software and is credited with inventing assembly language. But she also got her hands dirty with the hardware, having built a large portion of the computers which she programmed. She also did some early work with natural language processing and neural networks. And this was all before 1962, making her truly a pioneer. This then is her tale.

Early Years

Kathleen Booth was born Kathleen Britten in 1922 in Stourbridge, Worcestershire, England. She got a B.Sc. in Mathematics from the University of London and a Ph.D. in Applied Mathematics in 1950. There weren’t any computer degrees to be had as of yet. From 1944 to 1946 she was a Junior Scientific Office at the Royal Aircraft Establishment and then from 1946 to 1952, a Research Scientist at the British Rubber Producer’s Research Association (BRPRA). Also in 1946, she started work as a research assistant at Birkbeck College, University of London, later becoming a Research Fellow and Lecturer.

Building Computers At Birkbeck College

At Birkbeck, computer research was being done by Andrew Booth whom Kathleen would eventually marry. Andrew had previously done X-ray crystallography research at the University of Birmingham and that included doing a lot of computations. This started him down the path of building computing machines to make the work easier. He next spent a short time as a research physicist at the BRPRA where he began work on the ARC, the Automatic Relay Computer (sometimes referred to as the Automatic Relay Calculator). This used paper tape for input and was really a special purpose computer serving as a Fourier synthesizer.

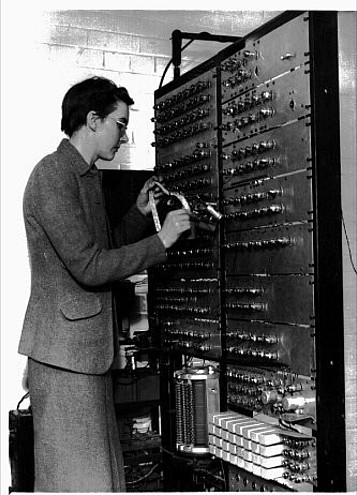

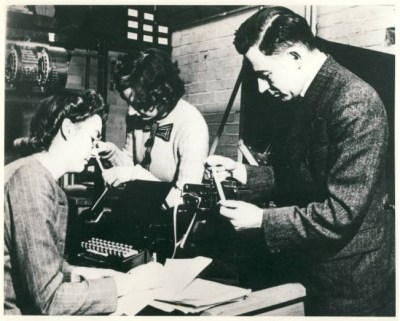

In 1946 he took up a post as a Nuffield fellow at Birkbeck. He continued work on the ARC but as there was no room at the College, and since the BRPRA was funding it, the work was done at their facilities. It was then that he met Kathleen. Kathleen and another research assistant, Xenia Sweeting, helped Andrew continue building the ARC and in fact did most of the construction.

6 Months In Princeton

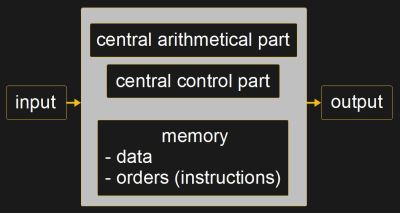

In 1945, John von Neumann wrote a document called the First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC wherein he described what became known as the von Neumann architecture for a computer. In it, he defines the parts of a computer and in particular that program is stored in the computer’s memory. For that reason, it’s also sometimes called the stored-program computer.

In 1945, John von Neumann wrote a document called the First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC wherein he described what became known as the von Neumann architecture for a computer. In it, he defines the parts of a computer and in particular that program is stored in the computer’s memory. For that reason, it’s also sometimes called the stored-program computer.

In 1947, through funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and the BRPRA, Andrew and Katheleen took a 6 month US tour with von Neumann whom Andrew had met during a previous visit. The tour was based in Princeton, New Jersey at the Institute for Advanced Study.

This visit was also the first time that the Booth’s had heard of the von Neumann architecture. It led Andrew to redesign the ARC, designing the relay part of the machine in only 2 months, coming up with what is sometimes referred to as the ARC2. Still in 1947, Kathleen and he also wrote up two reports about it, General considerations in the design of an all-purpose electronic digital computer and Coding for A.R.C.. The first of those reports was widely circulated and even underwent a 2nd edition. In it, they detailed what’s needed for a von Neumann architecture machine, outlining a number of different options for the memory.

Inventing Early Assembly Language

The only place I could find Coding for A.R.C. was as a hard copy on the Institute’s shelves, which is unfortunate as it’s usually the reference for where Kathleen first outlined her assembly language, or autocode, for ARC2. She also wrote the assembler for it.

The only place I could find Coding for A.R.C. was as a hard copy on the Institute’s shelves, which is unfortunate as it’s usually the reference for where Kathleen first outlined her assembly language, or autocode, for ARC2. She also wrote the assembler for it.

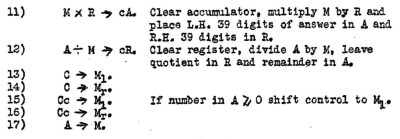

The other report was released around the same time, and while it does give a contracted notation for the ARC2’s machine language, I suspect that this wasn’t the assembly language. In that report, she first explains how the orders, which we now call instructions, are represented by 0s and 1s loaded into some sort of storage. For the ARC2, 10011 was the order to clear the arithmetic register and transfer a value from memory into the register. Today, we call this machine language. In contracted notation, she then gives the same order as M -> cR.

The Electronic Computers

Andrew Booth’s next computer was entirely electronic and called the SEC (Simple Electronic Computer). That was followed by the APE(*)C (All Purpose Electronic Computer) where the * was to be replaced by a letter representing the sponsor.

Katherine also wrote software for those two computers but unlike with ARC and ARC2, she didn’t do any of the construction.

Natural Language Processing

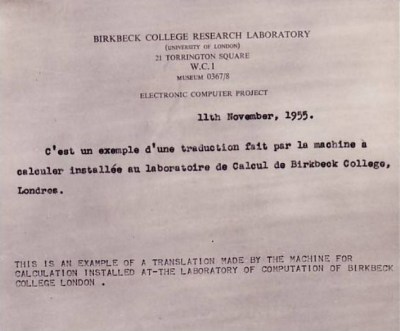

In 1947, in order to get funding from Rockefeller, the Booth’s added working on natural language processing to their list of projects. The goal was to achieve accurate technical translation and not literary quality. In their book, Automatic Digital Calculators, they outline some of the algorithms which they and collegues had worked on up to 1965, starting out with word substitutions and processing of stems and word endings. While they did a lot of work on NLP at Birkbeck College with their students, there’s also a record of them working on English-French translations for the National Research Council Canada between 1965 and 1972.

Neural Networking In The 1950s

As another example of her pioneering work, the Birkbeck College Annual Report of 1958/59 says that Kathleen wrote a program to simulate a neural network investigating ways in which animals recognize patterns and that the following year’s report mentions her work on a neural network for character recognition. This was only four years after the first running of a neural network on a computer.

Off To Canada

The Booth’s left Birkbeck College in 1962, both moving to Canada to work at the University of Saskatchewan and then at Lakehead University in 1972. She retired from Lakehead in 1978 but an article search shows a paper by her and her son, Dr. Ian J. M. Booth, entitled Using neural nets to identify marine mammals dated 1993 when she would have been 71 and still going strong.