Gaggle’s software monitors students’ use of school-issued accounts. But educators may not be prepared to respond to what they learn

A week after the pandemic forced Minneapolis students to attend classes online, the city school district’s top security chief got an urgent email, its subject line in all caps, alerting him to potential trouble. Just 12 seconds later, he got a second ping. And two minutes after that, a third.

In each instance, the emails warning Jason Matlock of “QUESTIONABLE CONTENT” pointed to a single culprit: Kids were watching cartoon porn.

Over the next six months, Matlock got nearly 1,300 similar emails from Gaggle, a surveillance company that monitors students’ school-issued Google and Microsoft accounts. Through artificial intelligence and a team of content moderators, Gaggle tracks the online behaviors of millions of students across the U.S. every day. The sheer volume of reports was overwhelming at first, Matlock acknowledged, and many incidents were utterly harmless. About 100 were related to animated pornography and, on one occasion, a member of Gaggle’s remote surveillance team flagged a fictional story that referenced “underwear.”

Hundreds of others, however, suggested imminent danger.

In emails and chat messages, students discussed violent impulses, eating disorders, abuse at home, bouts of depression and, as one student put it, “ending my life.” At a moment of heightened social isolation and elevated concern over students’ mental health, references to self-harm stood out, accounting for nearly a third of incident reports over a six-month period. In a document titled, “My Educational Autobiography, ” students at Roosevelt High School on the south side of Minneapolis discussed bullying, drug overdoses, and suicide. “Kill me, ” one student wrote in a document titled “goodbye.”

Nearly a year after The 74 submitted public records requests to understand the Minneapolis district’s use of Gaggle during the pandemic, a trove of documents offer an unprecedented look into how one school system deploys a controversial security tool that grew rapidly during COVID-19, but carries significant civil rights and privacy implications.

The data, gleaned from those 1,300 incident reports in the first six months of the crisis, highlight how Gaggle’s team of content moderators subject children to relentless digital surveillance long after classes end for the day, including on weekends, holidays, late at night and, over the summer. In fact, only about a quarter of incidents were reported to district officials on school days between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., bringing into sharp relief how the service extends schools’ authority far beyond their traditional powers to regulate student speech and behavior, including at home.

Now, as COVID-era restrictions subside and Minneapolis students return to in-person learning this fall, a tool that was pitched as a remote learning necessity isn’t going away anytime soon. Minneapolis officials reacted swiftly when the pandemic engulfed the nation and forced students to learn from the confines of their bedrooms, paying more than $355,000—including nearly $64,000 in federal emergency relief money—to partner with Gaggle until 2023. Faced with a public health emergency, the district circumvented normal procurement rules, a reality that prevented concerned parents from raising objections until after it was too late.

A mental health dilemma

With each alert, Matlock and other district officials were given a vivid look into students’ most intimate thoughts and online behaviors, raising significant privacy concerns. It’s unclear, however, if any of them made kids safer. Independent research on the efficacy of Gaggle and similar services is all but nonexistent.

When students’ mental health comes into play, a complicated equation emerges. In recent years, schools have ramped up efforts to identify and provide interventions to children at risk of harming themselves or others. Gaggle executives see their tool as a key to identify youth who are lamenting over hardships or discussing violent plans. On average, Gaggle notifies school officials within 17 minutes after zeroing in on student content related to suicide and self-harm, according to the company, and officials claim they saved more than 1,400 lives during the 2020–21 school year.

“As a parent you have no idea what’s going on in your kid’s head, but if you don’t know you can’t help them, ” said Jeff Patterson, Gaggle’s founder and CEO. “And I would always want to err on trying to identify kids who need help.”

Critics, however, have questioned Gaggle’s effectiveness and worry that rummaging through students personal files and conversations—and in some cases outing students for exhibiting signs of mental health issues including depression—could backfire.

Using surveillance to identify children in distress could exacerbate feelings of stigma and shame and could ultimately make students less likely to ask for help, said Jennifer Mathis, the director of policy and legal advocacy at The Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law in Washington, D.C.

“Most kids in that situation are not going to share anything anymore and are going to suffer for that, ” she said. “It suggests that anything you write or say or do in school—or out of school—may be found and held against you and used in ways that you had not envisioned.”

Minneapolis parent Holly Kragthorpe-Shirley had a similar concern and questioned whether kids “actually have a safe space to raise some of their issues in a safe way” if they’re stifled by surveillance.

In Minneapolis, for instance, Gaggle flagged the keywords “feel depressed” in a document titled “SEL Journal, ” a reference to social-emotional learning. In another instance, Gaggle flagged “suicidal” in a document titled “mental health problems workbook.”

District officials acknowledged that Gaggle had captured student assignments and other personal files, an issue that civil rights groups have long been warning about. The documents obtained by The 74 put hard evidence behind those concerns, said Amelia Vance, the director of Youth and Education Privacy at The Future of Privacy Forum, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

“The hypotheticals we’ve been talking about for a few years have come to fruition, ” she said. “It is highly likely to undercut the trust of students, not only in their school generally, but in their teacher, in their counselor—in the mental health problems workbook.”

Patterson shook off any privacy reservations, including those related to monitoring sensitive materials like journal entries, which he characterized as “cries for help.”

“Sometimes when we intervene we might cause some challenges, but more often than not the kids want to be helped, ” he said. Though Gaggle only monitors student files tied to school accounts, he cited a middle school girl’s private journal in a success story. He said the girl wrote in a digital journal that she suffered with self-esteem issues and guilt after getting raped.

“No one in her life knew about this incident, and because she journaled about it, ” Gaggle was able to notify school officials about what they’d learned, he said. “They were able to intervene and get this girl help for things that she couldn’t have dealt with on her own.”

‘Needles in haystacks’

Tools like Gaggle have become ubiquitous in classrooms across the country, according to forthcoming research by the D.C.-based Center for Democracy & Technology. In a recent survey, 81% of teachers reported having such software in place in their schools. Though most students said they’re comfortable being monitored, 58% said they don’t share their “true thoughts or ideas” as a result, and 80% said they’re more careful about what they search online.

Such data suggest that youth are being primed to accept surveillance as an inevitable reality, said Elizabeth Laird, the center’s director of equity in civic technology. In return, she said, they’re giving up the ability to explore new ideas and learn from mistakes.

Gaggle, in business since 1999 and recently relocated to Dallas, monitors the digital files of more than 5 million students across the country each year, with the pandemic being very good for its bottom line. Since the onset of the crisis, the number of students surveilled by the privately held company, which does not report its yearly revenue, has grown by more than 20%. Through artificial intelligence, Gaggle scans students’ emails, chat messages, and other materials uploaded to students’ Google or Microsoft accounts in search of keywords, images, or videos that could indicate self-harm, violence, or sexual behavior. Moderators evaluate flagged material and notify school officials about content they find troubling—a bar that Matlock acknowledged is quite low as “the system is always going to err on the side of caution” and requires district administrators to evaluate materials’ context.

In Minneapolis, Gaggle officials discovered a majority of offenses in files within students’ Google Drive, including in word documents and spreadsheets. More than half of incidents originated on the Drive. Meanwhile, 22% originated in emails and 23% came from Google Hangouts, the chat feature.

School officials are alerted to only a tiny fraction of student communications caught up in Gaggle’s dragnet. Last school year, Gaggle collected more than 10 billion items nationally, but just 360,000 incidents resulted in notifications to district officials, according to the company. Nationally, 41% of incidents during the 2020–21 school year related to suicide and self-harm, according to Gaggle, and a quarter centered on violence.

“We are looking for needles in haystacks to basically save kids, ” Patterson said.

‘A really slippery slope’

It was Google Hangouts that had Matt Shaver on edge. When the pandemic hit, classrooms were replaced by video conferences and casual student interactions in hallways and cafeterias were relegated to Hangouts. For Shaver, who taught at a Minneapolis elementary school during the pandemic, students’ Hangouts use became overwhelming.

Students were so busy chatting with each other, he said, that many had lost focus on classroom instruction. So he proposed a blunt solution to district technology officials: Shut it down.

“The thing I wanted was ‘Take the temptation away, take the opportunity away for them to use that, '” said Shaver, who has since left teaching and is now policy director at the education reform group EdAllies. “And I actually got pushback from IT saying ‘No we’re not going to do that, this is a good social aspect that we’re trying to replicate.'”

But unlike those hallway interactions, nobody was watching. Matlock, the district’s security head, said he was initially in the market for a new anonymous reporting tool, which allows students to flag their friends for behaviors they find troubling. He turned to Gaggle, which operates the anonymous reporting system SpeakUp for Safety, and saw the company’s AI-powered digital surveillance tool, which goes well beyond SpeakUp’s powers to ferret out potentially alarming student behavior, as a possibility to “enhance the supports for students online.”

“We wanted to get something in place quickly, as we were moving quickly with the lockdown, ” he said, adding that going through traditional procurement hoops could take months. “Gaggle had a strong national presence and a reputation.”

The district signed an initial six-month, $99,603 contract with Gaggle just a week after the virus shuttered schools in Minneapolis. Board of Education Chair Kim Ellison signed a second, three-year contract at an annual rate of $255,750 in September 2020.

The move came with steep consequences. Though SpeakUP was used just three times during the six-month window included in The 74’s data, Gaggle’s surveillance tool flagged students nearly 1,300 times.

During that time, which coincided with the switch to remote learning, the largest share of incidents — 38 percent — were pornographic or sexual in nature, including references to “sexual activity involving a student, ” professional videos and explicit, student-produced selfies which trigger alerts to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

An additional 30 percent were related to suicide and self-harm, including incidents that were triggered by keywords including “cutting, ” “feeling depressed, ” “want to die, ” and “end it all.” an additional 18 percent were related to violence, including threats, physical altercations, references to weapons and suspected child abuse. Such incidents were triggered by keywords including “Bomb, ” “Glock, ” “going to fight, ” and “beat her.” About a fifth of incidents were triggered by profanity.

Concerns over Gaggle’s reach during the pandemic weren’t limited to Minneapolis. In December 2020, a group of civil rights organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California argued in a letter that by using Gaggle, the Fresno Unified School District had violated the California Electronic Communications Privacy Act, which requires officials to obtain search warrants before accessing electronic information. Such monitoring, the groups contend, infringe on students’ free-speech and privacy rights with little ability to opt out.

Shaver, whose students used Google Hangouts to the point of it becoming a distraction, was alarmed to learn that those communications were being analyzed by artificial intelligence and poured over by a remote team of people he didn’t even know.

“I’m trying to imagine finding out about this as a high schooler, that every single word I’ve written on a Google Hangout or whatever is being monitored, ” he said. “There is, of course, some lesson in this, obviously like, ‘Be careful of what you put online.’ But we live in a country with laws around unreasonable search and seizure—and surveillance is just a really slippery slope.”

The potential to save lives

To Matlock, Gaggle is a lifesaver—literally. When the tool flagged a Minneapolis student’s suidice note in the middle of the night, Matlock said he rushed to intervene. In a late-night phone call, the security chief said he warned the unnamed parents, who knew their child was struggling but didn’t fully recognize how bad things had become. Because of Gaggle, school officials were able to get the student help. To Matlock, the possibility that he saved a student’s life offers a feeling he “can’t even measure in words.”

“If it saved one kid, if it supported one caregiver, if it supported one family, I’ll take it, ” he said. “That’s the bottom line.”

Despite heightened concern over youth mental health issues during the pandemic, its effect on youth suicide rates remains fuzzy. Preliminary data from the Minnesota health department show a significant decline in suicides statewide during the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2020, suicides among people 24 years old and younger decreased by more than 20% statewide. Nationally, the proportion of youth emergency-room visits related to suspected suicide attempts has surged during the pandemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but preliminary mortality data for people of all ages show a 5.6% decline in self-inflicted fatalities in 2020 compared to 2019.

Meanwhile, Gaggle reported that it identified a significant increase of threats related to suicide, self-harm, and violence nationwide between March 2020 and March 2021. During that period, Gaggle observed a 31% increase in flagged content overall, including a 35% increase in materials related to suicide and self-harm. Gaggle officials said the data highlight a mental health crisis among youth during the pandemic. But other factors could be at play. Among them is a 50% surge in students’ screen time during the pandemic, creating additional opportunities for Gaggle to tag youth behavior. Meanwhile, the number of students monitored by Gaggle nationally grew markedly during the pandemic.

But that hasn’t stopped Gaggle from citing pandemic-era mental illness in sales pitches as it markets a new service: Gaggle Therapy. In school districts that sign up for the service, students who are flagged by Gaggle’s digital monitoring tool are matched with counselors for weekly teletherapy sessions. Therapists available through the service are independent contractors for Gaggle, and districts can either pay Gaggle for “blanket coverage, ” which makes all students eligible, or a “retainer fee, ” which allows them to “use the service as you need it, ” according to the company. Under the second scenario, Gaggle would have a financial incentive to identify more students in need of teletherapy.

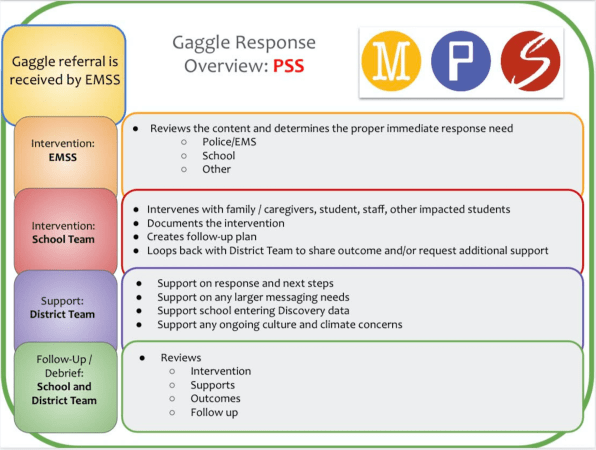

In Minneapolis, Matlock said that school-based social workers and counselors lead intervention efforts when students are identified for materials related to self-harm. “The initial moment may be a shock” when students are confronted by school staff about their online behaviors, he said, but providing them with help “is much better in the long run.”

As the district rolled out the service, many parents and students were out of the loop. Among them was Nathaniel Genene, a recent graduate who served as the Minneapolis school board’s student representative at the time. He said that classmates contacted him after initial news of the Gaggle contract was released.

“I had a couple of friends texting me like ‘Nathaniel, is this true?'” he said. “It was kind of interesting because I had no idea it was even a thing.”

Yet as students gained a greater awareness that their communications were being monitored, Matlock said they began to test Gaggle’s parameters using potential keywords, “and then say ‘Hi’ to us while they put it in there.”

As students became conditioned to Gaggle, “the shock is probably a little bit less, ” said Rochelle Cox, an associate superintendent at the Minneapolis school district. Now, she said students have an outlet to get help without having to explicitly ask. Instead, they can express their concerns online with an understanding that school officials are listening. As a result, school-based mental health professionals are able to provide the care students need, she said.

Mathis, with The Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, called that argument “ridiculous.” Officials should make sure that students know about available mental health services and ensure that they feel comfortable reaching out for help, she said.

“That’s very different than deciding that we’re going to catch people by having them write into the ether and that’s how we’re going to find the students who need help, ” she said. “We can be a lot more direct in communicating than that, and we should be a lot more direct and a lot more positive.”

In fact, subjecting students to surveillance could push them further into isolation, and condition them to lie when officials reach out to inquire about their digital communications, argued Vance of the Future of Privacy Forum.

“Effective interventions are rarely going to be built on that, you know, ‘I saw what you were typing into a Google search last night’ or ‘writing a journal entry for your English class, '” Vance said. “That doesn’t feel like it builds a trusting relationship. It feels creepy.”

This article was also published at The74 Million.org, a nonprofit education news site.

[Photo: Thomas Park/Unsplash]