https://www.genderit.org/feminist-talk/5-reasons-why-surveillance-feminist-issue

“Collecting and storing data is never a neutral act, and neither are data analysis or predictive modelling”

Republished with permission from the LSE Engenderings blog

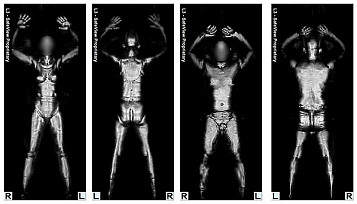

Above is a public domain image of full body scanning by millimeter wave technology sourced from here

Surveillance is woven into our everyday lives. While this in itself is not new, what we experience today differs in scale from, say, covert surveillance photos of suffragettes, tabs on unions and protesters during the Cold War era, or even the practices of the GDR’s Stasi.

Given the sheer variety and quantity of data constantly accumulated about any one of us, De Lillo’s ( 1985) fictional speculation that “you are the sum total of your data” has proven quite visionary. To speak of the informatisation of the body, data doubles, or data bodies is no longer fiction but scholarship.

Contemporary surveillance practices are to a large extent big data driven, underpinned by a collect-it-all logic, and ever expanding due to fear-mongering, yet pervasive national security discourse. Surveillance technologies and practices have not only multiplied in scale and quantity. They have also qualitatively transformed into an “assemblage” characterised by multiple sites of data collection and analysis, collaboration between different surveillance states as well as agencies, flesh/information flows, and the capacity for further expansion and variation. Others have been less eloquent and simply named the beast “surveillance industrial complex”.

While feminist work on surveillance is emerging academically as well as in activist circles, all too often feminist issues on the one hand, and discussions around privacy and surveillance on the other still feel like separate domains. What follows is my attempt at emphasising that thinking them together makes a lot of sense.

Collecting and storing data is never a neutral act, and neither are data analysis or predictive modelling.

1. Surveillance is about social justice

First off, a perhaps blatantly obvious point worth re-stating: Surveillance is not a topic reserved for tech geeks and the security industry, it is decidedly a social justice issue.

Once, concerns about surveillance were couched primarily in the language of privacy and, possibly, freedom. (…) While these issues are still significant, it is becoming increasingly clear to many that they do not tell the whole story. For surveillance today sorts people into categories, assigning worth or risk, in ways that have real effects on their life-chances. Deep discrimination occurs, thus making surveillance not merely a matter of personal privacy but of social justice (Lyon 2003:1).

For surveillance today sorts people into categories, assigning worth or risk, in ways that have real effects on their life-chances.

Thinking about/against surveillance necessarily involves questioning its underlying power relations and moving away from a blind belief in the objectivity of data and algorithms. Collecting and storing data is never a neutral act, and neither are data analysis or predictive modelling. A few years ago Laurie Penny argued that surveillance and patriarchy function in fairly similar ways, and that therefore the fight for the principles of free speech, the fight against surveillance and the fight for a society where whistleblowers are protected, is a feminist fight

Feminist work has decades of experience in dealing with precisely such questions in different contexts. An insistence that power relations matter, situated knowledges, critiques of objectivity, feminist science and technology studies, intersectionality, work around agency and coercion, and vast experience in interdisciplinary work taken together make a great toolkit to intervene in the gendered, racialised, and classed effects of surveillance practices.

2. The problem with categories

Categorisations along the lines of gender and sexualities and their intersections with class, race, and other differentiations have long been feminist issues for very good reasons. The same scrutiny of categories needs to be applied to their use in technologies of surveillance, where their normalising effects are no less chilling than elsewhere.

Contemporary surveillance heavily relies on statistical categories and algorithms, resulting in effective mechanisms of social sorting. In addition to gaps in the data that are filled by assumptions (guess who’s), statistical categories by definition operate by proximity to a norm. Unsurprisingly, the unspoken norm all data bodies are measured against is once again white cis-male heterosexuality.

Take for example full body scanners at international airports and how they disproportionately affect particular bodies, including people with disabilities, genderqueer bodies, racialised groups or religious minorities. To illustrate how algorithms are by no means neutral we can also revisit the discussions of Google image search results for “unprofessional hair” (hint: black women with natural hair), “women” or “men” (hint: normatively pretty white people). Whether we argue that Google’s search algorithm is racist per se, or concede that it merely reflects the racism of wider society – the end result remains far from neutral.

As Conrad (2009) notes, predictive models fed by surveillance data necessarily reproduce past patterns. They cannot take into effective consideration randomness, ‘noise’, mutation, parody, or disruption unless those effects coalesce into another pattern. More generally, the effects of surveillance on non-normative bodies and marginalised groups – particularly when read and sorted through potentially racist, heterosexist, or Islamophobic algorithms – warrant queer feminist interventions.

More generally, the effects of surveillance on non-normative bodies and marginalised groups – particularly when read and sorted through potentially racist, heterosexist, or Islamophobic algorithms – warrant queer feminist interventions

3. Nothing to hide?

Despite many very convincing rebuttals of this narrative (for example here, here or here) as well as its attribution to prominent Nazis, the lazy retort of “I have nothing to hide” in the face of mass surveillance has not gone out of style. My favourite response comes from Edward Snowden (pictured here) and makes abundantly clear that this argument is a fallacy for all.

Its feminist implications, however, reach wider than immediately meets the eye. Governed by heteronormative institutions within borders that come with their own racialised and sexualised technologies of control, how much is safe to reveal and what must remain hidden is not equal for all.

Google CEO Eric Schmidt, exemplary rich white man, has prominently expressed the opinion that whoever feels they have something to hide should probably not be doing it in the first place. Beyond well documented concerns about involuntary exposure of non-normative sexuality and need for anonymity to maintain so-called safe spaces online – racialised, religious, and genderqueer minorities potentially risk much more than the average white person (let alone Eric Schmidt) by revealing everything.

Beauchamp for example discusses the implications of “nothing to hide” for trans* people for whom questions of stealth versus visibility take on multiple dimensions. While some negotiate a desire/need to remain hidden with medical and legal records that were never quite private, others’ compliant visibility risks complicity with national security discourse around who can “pass” as “safe” citizen or traveler (white middle class, conclusively gendered, and definitely not Muslim) and whose deviance from the norm becomes subject to policing. Those in less privileged positions receive the blame for their own exclusion and exploitation – if bad things happen to them as a result, it must be because they have something to hide (Andrejevic 2015:xvii).

4. Surveillance takes many forms

In addition to practices that are habitually considered surveillance, for example CCTV and drone footage, wiretapping or PRISM, a feminist perspective can draw attention to a much wider range of de facto surveillance. For all the necessary and important focus on data-based mass surveillance since the release of the Snowden files, it is important to keep in mind that more mundane practices need to remain part of the discussion – not least because they also leave data traces outside of our control.

it is important to keep in mind that more mundane practices need to remain part of the discussion – not least because they also leave data traces outside of our control

It is no coincidence that the first book on feminist surveillance studies considers fertility screenings, ultrasound images, birth certificates, surrogacy blogs, police photos of domestic violence and the likes as racialised, gendered, classed and sexualised technologies of surveillance alongside those traditionally considered surveillance proper. With a nod to bell hooks, the authors call the ways in which surveillance practices play into the hands of privilege “white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchal surveillance”.

Alongside work that firmly places race at the heart of surveillance studies, feminist perspectives enrich and complicate the ways we think about the technologies tracking our every move as well as which technologies we think about in the first place. Last but not least, my hope is that this broadening of the scope might further inspire a wider public to care about how various kinds of surveillance seep into every aspect of our lives.

With a nod to bell hooks, the authors call the ways in which surveillance practices play into the hands of privilege “white supremacist capitalist heteropatriarchal surveillance”.

5. Read number 3 again, it’s important!

Author: Nicole Shephard

Nicole Shephard is a feminist researcher and writer interested in the gender and tech nexus, surveillance, intersectionality and digital activism. She holds a PhD in Gender (LSE) and an MSc in International Development (University of Bristol). She tweets as @kilolo_.